Jamaica gender-based violence policy hub

This hub provides key facts about gender-based violence in Jamaica.

Gathering and updating this information will help to inform our own research in the area and, over time, influence policy to help reduce GBV. It will also help to inform the None in Three game aimed at young people in Jamaica. For more information and references, download our policy briefing sheet.

This Policy Brief is drawn from qualitative research with adult survivors of child sexual abuse (CSA) carried out by the None in Three Research Centre Jamaica during 2018-19. The research involved: in-depth interviews with 15 female survivors of child sexual abuse; two focus groups, one with male survivors and one with professionals who had worked with male survivors; and a review of systematic reviews of schools based, child-focused CSA preventative interventions.

Jamaica Policy Brief

Web Version

Read Online

Jamaica Policy Brief

Print Version

Read Online

Timeline of Jamaica’s most important legislation related to gender-based violence

The Domestic Violence Act – An act to provide remedies for domestic violence, for the protection of the victim through speedy and effective relief and for matters connected therewith and incidental thereto.

Criminal Justice Administration Act – Trials for rape, carnal knowledge and incest are held ‘in camera’ in order to make the judicial system less harrowing to victims of violence.

Domestic Violence Act (Amendment) – This amendment allows victims to apply for a protection order. It also makes a special provision for women involved in residential and non-residential relationships.

Married Women’s Property Act (Amendment) – An Act to amend the Married Women’s Property Law. It introduces a special family property regime for spouses to provide for the equitable division of property between spouses upon dissolution of marriage. Each spouse has a 50% share in the family home, which must be registered solely in one spouse’s name or in their joint names.

The Property (Rights of Spouses) Act, 2004 – An act to make provision for the division of property belonging to spouses.

Child Care and Protection Act – An Act to provide for the care and protection of children and young persons and for connected matters

The Domestic Violence Act (Amendment) – The Act provides for enhanced protection for victims of domestic violence and abuse and applies to both spouses and de facto (common law) spouses. The Act also now makes provision for persons in visiting relationships. It also allows for the Courts to issue Protection Orders, keeping the accused away from the home, work or school of the victim. Orders can be made on behalf of men, women or children affected by violence within the home.

The Maintenance Act – The Act makes provisions for maintenance within the family and confers equal rights and obligations on spouses with respect to the support of each other and their children.

Sexual Offences Act – An Act to repeal the Incest (Punishment) Act and certain provision of the Offences Against Person Act; to make new provision for the prosecution of rape and other sexual offences; to provide for the establishment of a Sex Offender Registry; and other connect matters.

Trafficking in Persons (Prevention, Suppression and Punishment) Amendment – An amendment to an Act originally introduced in 1971. An act to make provision for giving effect to the protocol to prevent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children.

The Child Pornography (Prevention) Act – An Act to prohibit the production, distribution, importation, exportation or possession of child pornography, and the use of children for child pornography, and to provide for connected matters.

The Offences Against the Person Act – This act is the primary source of sexual offence prohibitions and penalties in Jamaican law. Its approach to sexual offences is highly gender-specific, in that rape is defined as a non-consensual penetration of a vagina by a penis. Whosoever shall be convicted of the crime of rape shall be guilty of felony, and being convicted thereof, shall be liable to imprisonment for life.

The Sexual Offences Act – An Act to repeal the Incest (Punishment) Act and Sections 44-67 of the Offences Against Person Act; to make new provision for the prosecution of rape and other sexual offences; to provide for the establishment of a Sex Offender Registry; and other connect matters. It introduces other sexual offences, such as grievous sexual assault and marital rape.

The Evidence (Special Measures) Act – An Act to introduce special measures for giving of evidence by vulnerable witnesses.

Sexual Harassment Act – An Act to make provision for the prevention of sexual harassment and for connected matters.

An island country in the Caribbean, Jamaica has a population of approximately 3 million. Jamaica is currently classed as an upper-middle income nation according to the World Bank

Gender parity

Gender equality indices

Jamaica’s gender inequality index 2020

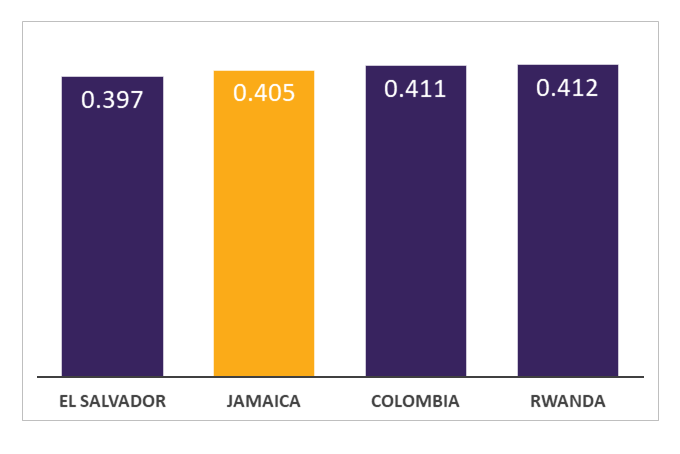

Gender Inequality Index (GII) measures gender inequalities between women and men in three important areas: reproductive health, empowerment, and economic status. Values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more disparities between the genders. Jamaica’s current GII index is 0.405. Comparable scores are currently held by El Salvador (0.397), Colombia (0.411), and Rwanda (0.412).

Jamaica’s global gender gap index (GGGI)

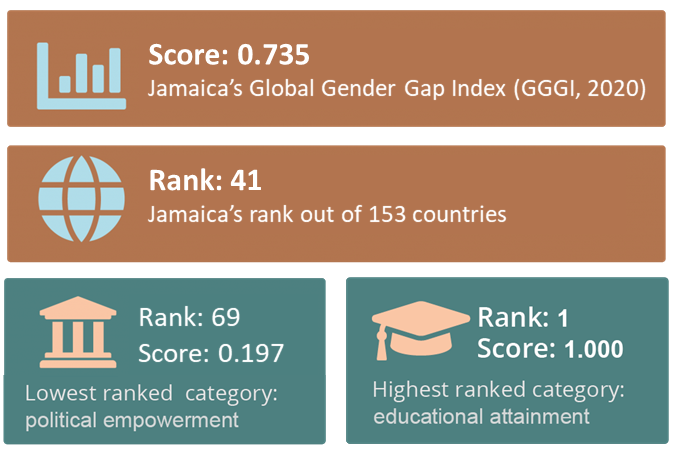

Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) assesses gender gaps on economic, political, education, and health criteria. Values range from 0 to 1, with lower values indicating more disparities between the genders. According to the Global Rankings Report 2020, Jamaica’s GGGI is 0.735 (rank 41 out of 153 countries), which indicates a slight improvement compared with last report. Jamaica recorded the highest rank on educational attainment (score: 1.000, rank: 1). The country’s lowest rank was on political empowerment (score: 0.197, rank: 69), followed by health and survival subindex (score: 0.976, rank: 65), and economic participation and opportunity (score: 0.767, rank: 24). Jamaica is one of four countries (including Bahamas, Colombia, and Honduras) which have achieved full gender parity on senior roles in the labour force.

Gender-based violence

UN Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Committee

In June 2013, the UN Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Committee expressed “its profound concern at high rates of domestic and sexual violence, and the lack of a comprehensive strategy to address the phenomenon” in Jamaica. There is no comprehensive statistical information available on the extent of different forms of GBV in Jamaica, but several reports note high rates of domestic and sexual violence and suggest that these crimes are underreported due to fear of shame, social stigma, disgrace, or further violence. As such, many women seek help only when violence becomes particularly severe. In a self-report study among 3124 high school students (1467 boys and 1657 girls), 44.7% participants reported having witnessed violence in their homes (Soyibo & Lee, 2000).

Intimate partner violence

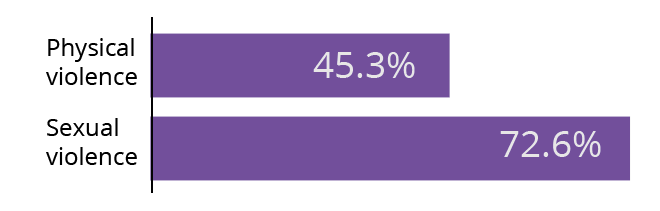

A 2008 study of 1402 men and women in Jamaica aged 15-30, found that 45.3% and 72.6% of Jamaican women experienced physical violence and sexual coercion respectively in the context of an intimate relationship (Le Franc, Samms-Vaughan, Hambleton, Fox, and Brown , 2008).

Research amongst 187 women who access the services of the Women’s Crisis Centre in Kingston demonstrates a high level of physical injury (89%) and a low level of reporting violent incidents to the police (26%) (Arscott-Mills, 2001).

Marital rape is not a statutory crime in Jamaica, which can partly explain underreporting of such violence to the police. Another form of GBV of deep concern in Jamaica is child sexual abuse (CSA).

Responding to GBV

Unlike in some other countries where GBV is widespread, authorities in Jamaica are generally willing to provide effective protection to women (Home Office, 2015). For example, in 2007, the Child Development Agency (CDA) launched a toll free telephone line to handle cases of human trafficking. In 1985, Jamaica ratified the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Nonetheless, there remains a lack of social programmes with sufficient scope to fully address the problem (Jones, Trotman Jemmott, Maharaj, & Da Breo, 2014; Miller, 2014). Indeed, although gender parity is addressed at structural level, it appears that there is still a need to tackle gender stereotyping and these efforts should start early in schools (for more information see Discrimination against Women UN meeting press release).

Child Maltreatment in Jamaica

Child maltreatment is a public health issue in all world regions, including the Caribbean. In a study with 2118 Jamaican children, 75.9% and 70.6% of children reported to have experienced psychological abuse and moderate physical abuse respectively in the month preceding completion of the questionnaire (Akmatov, 2011). In a survey of 15,695 students 10 to 18 years old from nine Caribbean nations, 47.6% of females and 31.9% of males described their first intercourse as forced or coerced and attributed blame to family members or individuals otherwise known to their family (Halcón, Blum, Beuhring, Pate, Campbell-Forrester, & Venema, 2003). Further, over the past few years, instances of child sexual abuse (CSA) in Jamaica have been steadily increasing. Most of these CSA cases involve contact abuse perpetrated by a variety of adults. According to official data, in 2004, teenage girls accounted for 70% of reported sexual assaults (Neufville, 2011). Sexual abuse is the third most prevalent reason for children seeking medical attention (Kirkland, 2012). A survey study among 100 Jamaican adults recruited from the community and medical centres indicated that those adults who reported having experienced CSA had an increased likelihood of developing sexual dysfunction in adulthood (Swaby & Morgan, 2007). Although CSA appears to be a widespread problem in Jamaica, it is mostly described in the local newspapers, which draw on official statistical data and some anecdotal accounts. More scientific research with large, representative Jamaican samples is warranted to explore this serious problem in greater depth.

GBV in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic in Jamaica

The introduction of social distancing and lockdown-type, stay-at-home measures has resulted in conditions conducive to physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of the most vulnerable members of the society. Those who are abused by family members, often have little or no access to the usual routes of escape. As such, the world has witnessed a surge in domestic violence cases since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Townsend, 2020). Although Jamaica’s largest residential facility for victims of domestic violence reported reduced number of calls to its hotlines during the pandemic, experts believe that it does not mean that the incidence of domestic violence has fallen. It may be that victims do not report domestic violence because they have other things to worry about, such as getting food, and/or do not feel safe to do this due to constant presence of the abuser in the home (Barrett, 2020). It is believed that the effect of the pandemic on domestic violence will become clearer once the lockdown-type measures have been lifted. There are also concerns for a greater risk of child sexual abuse (CSA) and other forms of child abuse during the pandemic. According to UNICEF Jamaica (2020), between January to June 2020, the National Children’s registry received over 1000 reports of sexual abuse for investigation. Radio Jamaica News (2020) reported that according to the Paediatric Association of Jamaica, there had been a 70% increase of CSA since the pandemic where adult men 40 to 50 years old are victimising girls three to 12 years old. Additionally, Kennedy (2020) stated that the island had experienced a high number of CSA cases since restrictions started in March. Kennedy noted that of 700 victims reported March and April, 16% of the cases were children 12 to 17 years old. This is an increase compared to previous years. António Guterres, the United Nations (UN) secretary-general, said: “I urge all governments to make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of their national response plans for COVID-19” (see Fang, 2020).

Jamaica’s action plan to eliminate GBV:

In 2017, the Government launched a 10-year National Strategic Action Plan to Eliminate Gender-Based Violence in Jamaica (NSAP-GBV) 2017-2027. The plan focuses on five interlinked priority areas: (1) prevention, (2) protection (psychosocial and health), (3) investigation, prosecution, and enforcement of court orders, (4) enforcement of victim’s rights to compensation, reparation, and redress, and (5) protocols for coordination of NSAP and data management systems. The plan indicates that data collection protocols and mechanisms will be standardised to assess the prevalence of GBV. Prevention strategies will be aimed at the whole population to transform people’s attitudes, behaviours, and practices which support violence against women. Effective prevention, it was noted, will ease the economic burden of GBV. The Bureau of Gender Affairs (BGA) under the coordination of the Ministry of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport (MCGES) will be the lead agency for the implementation of the NSAP- GBV.