United Kingdom gender-based violence policy hub

This hub provides key facts about gender based violence (GBV) in the UK. Gathering and updating this information will help to inform our own research in the area and, over time, influence policy to help reduce GBV. It will also help to inform the None in Three game aimed at young people in the UK. For more information and references, download our policy briefing sheet.

The Policy Briefs are drawn from research on intimate partner violence (IPV) conducted by the None in Three Research Centre UK. The primary research involved in-depth interviews with 52 female and 3 male survivors of IPV; and focus groups with 19 male perpetrators of IPV.

UK Policy Brief: Education to Prevent Intimate Partner Violence in the UK

Web Version

Read Online

UK Policy Brief: Improving Support & Justice for Victims of Intimate Partner Violence in the UK

Web Version

Read Online

Timeline of United Kingdom’s most important legislation related to gender-based violence

Domestic Violence and Matrimonial Proceedings Act – An Act to amend the law relating to matrimonial injunction; to provide the police with powers of arrest for the breach of injunction in cases of domestic violence; to amend section 1(2) of the Matrimonial Homes Act 1967; to make provision for varying rights of occupation where both spouses have the same rights in the matrimonial home.

Children Act – An Act to reform the law relating to children; to provide for local authority services for children in need and others; to amend the law with respect to children’s homes, community homes, voluntary homes and voluntary organisations; to make provision with respect to fostering, child minding and day care for young children and adoption; and for connected purposes.

1994 – Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (Amendments to the Sexual Offences Amendment Act 1976) – The Act criminalises marital rape.

Protection from Harassment Act – An Act to make provisions for protecting persons from harassment and similar conduct.

Female Genital Mutilation Act – An Act to restate and amend the law relating to female genital mutilation (FGM). Under the Act, carrying out, aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring the carrying out of FGM abroad, even in countries where the practice is legal, is an offence.

Sexual Offences Act – An Act to make new provision about sexual offences, their prevention and the protection of children from harm from other sexual acts, and for connected purposes. Rape within marriage is currently governed by section 1 of the Act.

Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act – An Act to amend Part 4 of the Family Law Act 1996, the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 and the Protection from Harassment (Northern Ireland) Order 1997; to make provision about homicide; to make common assault an arrestable offence; to make provision for the payment of surcharges by offenders; to make provision about alternative verdicts; to provide for a procedure under which a jury tries only sample counts on an indictment; to make provision about findings of unfitness to plead and about persons found unfit to plead or not guilty by reason of insanity; to make provision about the execution of warrants; to make provision about the enforcement of orders imposed on conviction; to amend section 58 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 and to amend Part 12 of that Act in relation to intermittent custody; to make provision in relation to victims of offences, witnesses of offences and others affected by offences; and to make provision about the recovery of compensation from offenders.

Children Act – An Act to make provision for the establishment of a Children’s Commissioner; to make provision about services provided to and for children and young people by local authorities and other persons; to make provision in relation to Wales about advisory and support services relating to family proceedings; to make provision about private fostering, child minding and day care, adoption review panels, the defence of reasonable punishment, the making of grants as respects children and families, child safety orders, the Children’s Commissioner for Wales, the publication of material relating to children involved in certain legal proceedings and the disclosure by the Inland Revenue of information relating to children.

Forced Marriage (Civil Protection Act) – An Act to make provision for protecting individuals against being forced to enter into marriage without their free and full consent and for protecting individuals who have been forced to enter into marriage without such consent; and for connected purposes.

Equality Act – An Act to make provision to require Ministers of the Crown and others when making strategic decisions about the exercise of their functions to have regard to the desirability of reducing socio-economic inequalities; to reform and harmonise equality law and restate the greater part of the enactments relating to discrimination and harassment related to certain personal characteristics; to enable certain employers to be required to publish information about the differences in pay between male and female employees; to prohibit victimisation in certain circumstances; to require the exercise of certain functions to be with regard to the need to eliminate discrimination and other prohibited conduct; to enable duties to be imposed in relation to the exercise of public procurement functions; to increase equality of opportunity; to amend the law relating to rights and responsibilities in family relationships; and for connected purposes.

Crime and Security Act – The Act contains a chapter on domestic violence (Sections 24 to 33). It provides for the issuance of Domestic Violence Protection Orders.

Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims (Amendment) Act – An Act to amend section 5 of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004 to include serious harm to a child or vulnerable adult; to make consequential amendments to the Act; and for connected purposes.

Protection of Freedoms Act – The Act made provision about the trafficking of people for exploitation and introduced two new offences for stalking. The offences cover stalking and stalking involving fear of violence or serious alarm and distress.

Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act -The Act criminalises forcing someone to marry against their will; criminalises the luring of a person to a territory of a state for the purpose of forcing them to enter into marriage; makes it an offence to use deception with the intention of causing another person to leave the UK for the intention of forcing that person to marry; criminalises the breach of a Forced Marriage Protection Order.

Serious Crime Act – Section 76 of the Act created a new offence of controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship. The offence carries a maximum sentence of 5 years’ imprisonment, a fine or both. Prior to the introduction of this offence, case law indicated the difficulty in proving a pattern of behaviour amounting to harassment within an intimate relationship.

Modern Slavery Act – An Act to make provision about slavery, servitude and forced or compulsory labour and about human trafficking, including provision for the protection of victims; to make provision for an Independent Anti-slavery Commissioner; and for connected purposes.

Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (Ratification of Convention) Act – An Act to make provision in connection with the ratification of the United Kingdom of the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (the Istanbul Convention). The Convention targets violence against women and domestic violence. It sets out minimum standards on prevention, protection, prosecution and services and states that countries ratifying the Convention must establish services such as hotlines, shelters, medical services, counselling and legal aid.

To advance gender equality in higher education and research, in 2005 the Equality Challenge Unit (ECU) established Athena SWAN Charter.

The United Kingdom (UK) is a country in Western Europe with a population of approximately 66 million. According to the World Bank country classifications by income level, the UK is currently classed as a high income nation (US$ 12,236 or more)

Gender parity

Gender equality indices

UK gender inequality index 2020

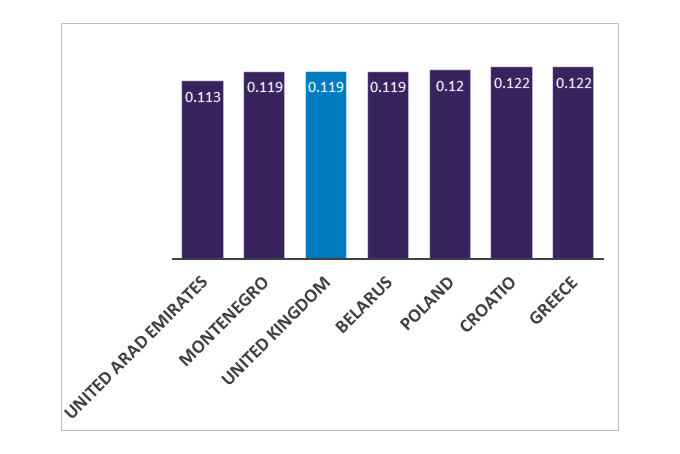

Gender Inequality Index (GII) measures gender inequalities between women and men in three important areas: reproductive health, empowerment, and economic status. Values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more disparities between the genders. The UK’s current GII index is 0.119. Countries with a similar score to the UK are: Croatia (0.122), Greece (0.122), Poland (0.120), Belarus (0.119), Montenegro (0.119), and United Arab Emirates (0.113).

UK global gender gap index (GGGI)

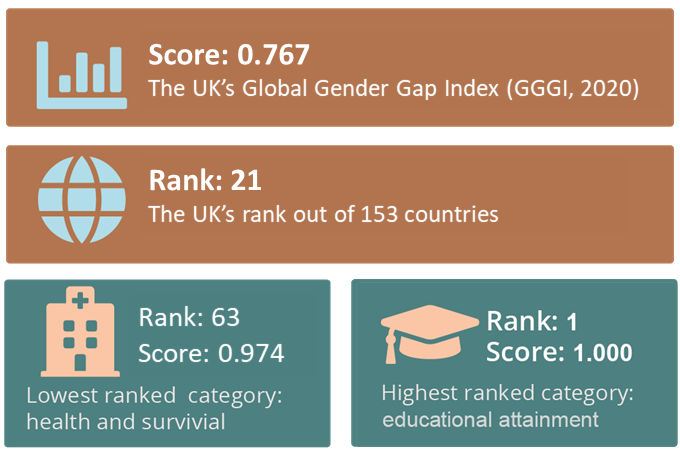

Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) assesses gender gaps on economic, political, education, and health criteria. Values range from 0 to 1, with lower values indicating more disparities between the genders. According to the Global Rankings Report 2020, the UK’s GGGI is 0.767 (rank 21 out of 153 countries). Compared with previous report published in 2018, the UK’s rank on the GGGI dropped by 6 ranks. The UK was ranked the highest on educational attainment subindex (score: 1.000, rank = 1). Compared with previous report, the UK has marked an improvement on its most problematic category, i.e., health and survival (previous score: 0.970, previous rank: 110 vs. current score: 0.974, current rank: 63).

Gender-based violence

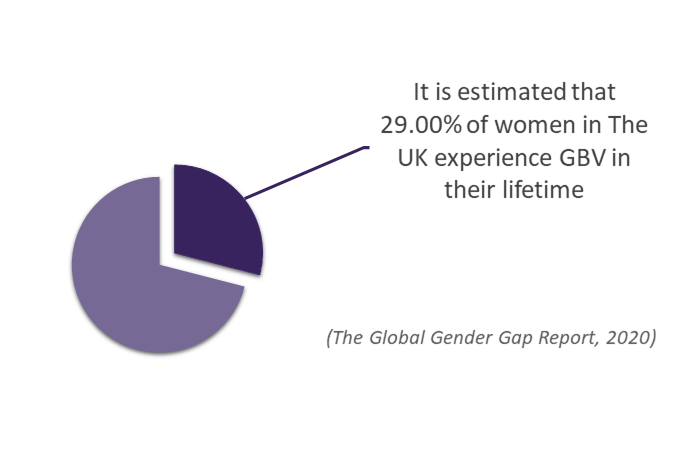

Women, compared with men, were more likely to experience all types of domestic abuse, except for non-sexual family abuse where the difference between the two sexes was statistically non-significant. As for lifetime prevalence, it is estimated that 26% of women and 15% of men aged 16 to 59 had experienced domestic abuse since the age of 16.

Walby (2009) estimates that providing public services to victims of domestic violence and the lost economic output of women affected costs the UK £15.8 billion annually. The cost to health, housing and social services, criminal justice and civil legal services is estimated at £3.9 billion.

Adolescent violence

Findings of another study among young people aged between 15 and 18 years from England (N = 199) and Spain (200) indicated that 25% of English girls occasionally experienced mild victimisation. The same proportion of girls also reported more severe physical victimisation. English boys appear to experience similar levels of occasional mild victimisation (20.5%) but substantially lower rates of occasional severe victimisation (5.1%) than girls.

GBV crime statistics

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) published in 2018 revealed that 7.5% of women and 4.3% of men suffered any type of domestic abuse between April 2016 and March 2017.

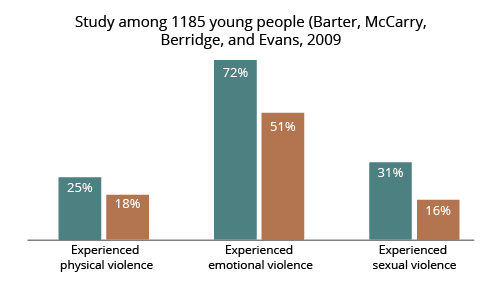

GBV, however, is not limited to adult relationships. The prevention of adolescent violence has been on UK’s political agenda since the 1990s but research on dating violence among UK samples has been sparse. Addressing this significant knowledge gap, a study among 1185 young people who had at least one relationship experience, demonstrated that a quarter of girls (n = 150) and 18% (n = 100) of boys were exposed to some form of physical violence by a partner. Girls were also more likely than boys to report negative impact (such as feeling humiliated and upset) of such violence. Emotional violence was reported by 72% of girls and 51% of boys. Experiences of sexual violence, on the other hand, were reported by 31% of girls and 16% of boys (Barter, McCarry, Berridge, & Evans, 2009).

Responding to GBV

Thanks to the introduction of the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme (DVDS) – also known as Clare’s Law – in 2014, women now have a right to know (in prescribed circumstances) if their partner has a violent past. The law means women can be protected by new domestic violence protection orders (DVPOs). Additionally, in 2018, the government conducted a consultation among domestic violence survivors, professionals, and local authorities in order to seek their views on legislative proposals for a landmark draft Domestic Abuse Bill and a package of practical action. In considering UK’s multiculturalism, GBV can take many different forms. Types of violence which predominantly affect women from ethnic minorities include female genital mutilation (FGM), forced marriage, and ‘honour’-based violence. Although all the above are now regarded as GBV and have been outlawed, they were initially treated as condemnable cultural practices. The UK ratified the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 1986.

UK’s strategy to end violence against women and girls (VAWG):

In 2016, the UK government published a new strategy to tackle violence against women and girls to be implemented between 2016-2020. One of the key aspects of the strategy is the strengthening of the legislative framework. To achieve this goal, new offences have been introduced to tackle stalking, coercive and controlling behaviour, as well as forcing someone to marry against their will. The foundation of the strategy, however, is prevention and early intervention. Prevention efforts include educating young people about healthy relationships, abuse, and consent. To support the activities, the government have pledged £80 million in funding. It is envisaged that by 2020, there will be a significant reduction in the number of VAWG victims and that women and girls with violence experiences will be able to access the support they need.

GBV in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK

The introduction of social distancing and lockdown-type, stay-at-home measures has resulted in conditions conducive to physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of the most vulnerable members of the society. Those who are abused by family members, often have little or no access to the usual routes of escape. Additionally, fewer visitors to the household means that evidence of physical abuse is more likely to go unnoticed. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the world has witnessed a surge in domestic violence cases since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Townsend, 2020). Indeed, emerging evidence from agencies across the UK reveals that domestic violence has increased during the COVID-19 crisis. The National Domestic Abuse helpline reported a 25% increase in calls and online requests since the lockdown began in March 2020 (Kelly & Morgan, 2020). However, it is believed that the effect of the pandemic on domestic violence will become clearer once the lockdown-type measures have been lifted.

In acknowledging that certain lockdown measures can increase the risk of domestic abuse, the Government announced that household isolation instructions do not apply if a person needs to leave their home to escape domestic abuse. In June 2020, the Social Care Institute for Excellence published a quick guide aimed at professionals and organisations who are involved in supporting and safeguarding adults and children during the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, national charities produced their own guidance and continue to provide their services to those in need. For example, SafeLives prepared a document entitled “Staying safe during COVID-19: A guide for victims and survivors of domestic abuse”. All national helplines are free to call and can provide interpreter services if needed. Safety and wellbeing advice, along with a list of national helplines, can be found here. Finally, António Guterres, the United Nations (UN) secretary-general, said: “I urge all governments to make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of their national response plans for COVID-19” (see Fang, 2020).