The Ni3 Brazil ‘Emilio’ project, funded through the End Violence ‘Safe Online’ programme, addresses youth-perpetrated online child sexual abuse. While there are many different forms of sexual violence committed online (including cyberbullying, revenge pornography, ‘slut-shaming’), our research and educational game specifically focus on the harm that can arise from the widely adopted practice of ‘sexting’ or sharing ‘nudes’ and intimate sexual text messages.

Brazil policy hub

Key facts about online youth perpetrated sexual abuse in Brazil

Gathering and updating this information will help to inform our own research in the area and, over time, influence policy to help reduce GBV and online abuse. It will also help to inform the None in Three game aimed at young people in Brazil.

Ni3 Emilio: Tackling Youth-Perpetrated Online Child Sexual Abuse

In Brazil, ‘the expression sexting is associated with the sending of images of the body, popularly known as “nudes”, slang used by young people to refer to images with sexual content received or sent’.[1] Although sexting may be consensual, it can itself be, and can lead to, sexual violence and since the victims themselves tend to be young people this will typically be classed as instances of peer-perpetrated child sexual abuse.

The issue was brought to wide public attention in Brazil in 2013 when a 17-year-old committed suicide after having an intimate video shared online without their permission.[2]

SaferNet Brasil[3] report that the third most common request for help they receive is for issues arising from sexting. Plan International, in its Freedom Online survey[4], gathered data on online harassment experienced by children and adolescents in Brazil. They found that 77% of girls reported being harassed, compared to a global average of 58%.[5] The main social media platforms through which participants reported suffering harassment were Facebook (62%), Instagram (44%) and WhatsApp (40%).

Access to online spaces

In 2017, 74.9% of the Brazilian population had access to the internet (and 88.4% of young people aged 20 to 24).[6] Data indicates[7]:

- cell phones were the most used device to access the internet at home in 97.0% of the population

- 5% of people over 10 years old accessed the internet in 2017 to send or receive text, voice or image messages via messaging apps, excluding email apps

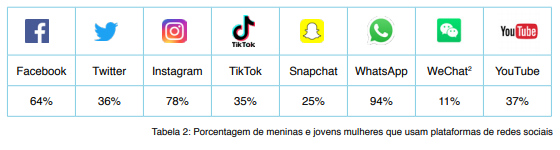

According to the Plan International report ‘Freedom online?’, the social media platforms used by most girls in Brazil are the same as those used most by the general public, namely WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook.

WhatsApp and Snapchat were highlighted in a 2019 study by UNICEF as the commonly used platforms for sexting.[8]

Image credit: Plan International, Liberdade on-line? 2021.

Negative outcomes associated with sexting in Brazil

According to literature on the topic, the main negative results of sexting in Brazil include:

- psychological, social and functional impairments, such as impacts on mental health

- suicidal ideation

- being a victim of insults and name-calling and being seen as ‘guilty’ of sharing intimate photos

- problems at school, or needing to change schools and/or other environments, after having intimate photos exposed

- becoming physically insecure

- low self-esteem, loss of confidence

- mental or emotional stress

- problems with friends or family

According to the report Violence, suicide and crimes against the honor of women on the internet[9], from the Women’s Secretariat of the Chamber of Deputies, 127 women and girls killed themselves in Brazil because of online ‘exposure’ between 2015 and 2017.

Brazilian legislation regarding sexting and its potential negative results

The report Girls in a network by Safernet (in partnership with UNICEF, 2021), lists laws of the Brazilian Penal Code which protect and guarantee individual rights when online[10].

Maria da Penha Law (11.340), August 2003: Domestic violence is not just physical aggression. Law 11.340 exists to protect women from domestic abuse and can also be applied in the digital context. Threats and coercion by social networks and messaging apps can be used as evidence in lawsuits that include requests for protective measures.

Child pornography (Law 11.829), November 2008: acquiring, owning or storing, offering, exchanging, making available, transmitting, distributing, publishing or disseminating, by any means, an explicit sex scene or nudity of minors is a crime. Passed in 2008, Law 11.829 updated previous legislation (8069, July 1990) and perpetrators can receive sentences of 4 to 8 years’ imprisonment, as well as a fine.

Carolina Dieckmann Law (12.737), November 2012: Was created to inhibit cybercrime, regardless of the victim’s gender. It can also be applied to protect girls who have their cell phone, or other devices, hacked and their contents misused. The punishment ranges from 3 months to 1 year of imprisonment, in addition to a fine.

Lola Law (13.642) April 2018: Law 13.642 / 2018 gave federal police powers to investigate cyber-crimes that spread misogynist content against women.

Law of nudes (13.718), September 2018: Since 2018, disclosing a nude photo, nude video or sex scene without the consent of the person who appears in the images is a crime according to Law 13.718 carrying a sentence of 1 to 5 years’ imprisonment. If the perpetrator has or had any relationship with the victim, it is an aggravating factor. If the victim is a minor, the punishment is more severe.

Sexual harassment (13.718), 2018: Law 13.718 / 18, which deals with sexual harassment, carries a penalty of 1 to 5 years’ imprisonment and is the most common type of violence that affects girls on the internet.[11]

Sexual harassment and disclosure of rape scenes are now crimes. The crime of sexual harassment is characterised by performing a libidinous act in the presence of someone and without their consent. The most common case is harassment suffered by women on public transport, such as buses and subways. Previously, this was considered only a criminal misdemeanor, with a fine. Now, those who engage in such behaviour could face 1 to 5 years in prison.

Anyone who sells or discloses a rape scene by any means, whether photography, video or any other type of audiovisual record, may also receive the same penalty. The penalty will be even greater if the aggressor has an emotional relationship with the victim.

Existing interventions

The current literature indicates the scarcity of data relating to interventions in Brazilian schools to prevent harm related to sexting, however the following couple of studies provide some useful insights.

In response to UNICEF’s 2019 survey, 70% of Brazilian girls said sexting had never been discussed at school[12]. Of those who said their school had dealt with the topic:

- 38% said that it was approached in the classroom

- 28% said it was brought up by students

- 21% saw the subject being addressed by external speakers invited into school

- 10% reported that the theme was worked on in school projects

References

- Souza, Lara & Lordello Sílvia, 2020

- Available on: https://www.unicef.org/brazil/media/1671/file/Adolescentes_e_o_risco_de_vazamento_de_imagens_intimas_na_internet.pdf

- Available on: https://new.safernet.org.br/helpline

- Available on: https://plan.org.br/liberdade-on-line/

- Plan International: https://brasilpaisdigital.com.br/estudo-global-aponta-que-58-das-meninas-ja-sofreram-assedio-on-line-no-brasil-numero-chega-a-77/

- UNICEF. ‘Caretas: Adolescentes e o risco de vazamento de imagens íntimas na internet’, 2019.

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 2018, Available on: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-37722020000100503&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt

- ibid

- Available on: https://www2.camara.leg.br/atividade-legislativa/comissoes/comissoes-permanentes/comissao-de-defesa-dos-direitos-da-mulher-cmulher/arquivos-de-audio-e-video/apresentacao-ap-280917-crimes-ciberneticos_janara

- Available on: https://www.unicef.org/brazil/relatorios/meninas-em-rede

- https://vogue.globo.com/assedio/noticia/2021/10/assedio-e-violencia-de-genero-que-mais-atinge-mulheres-em-todo-o-mundo.html

- UNICEF. ‘Caretas: Adolescentes e o risco de vazamento de imagens íntimas na internet’, 2019.